Where Midwest Floods Have the Most Impact on Acres Planted

As deadly flooding hits parts of the Midwest and inflicts major damage to its farm economy, one area yet to feel the brunt of expected floods is the Red River basin, including North Dakota, the state with one of the highest rates of weather-prevented planting.

As deadly flooding hits parts of the Midwest and inflicts major damage to its farm economy, one area yet to feel the brunt of expected floods is the Red River basin, including North Dakota, the state with one of the highest rates of weather-prevented planting.

Prevent-planting represents acreage that farmers are unable to sow because of severe weather or overly wet conditions. It not only affects producers forced to forgo revenues from unplanted fields, but also seed, fertilizer, and other input companies that will see reduced demand. Crop insurance companies, whose policies designate final planting dates, also have to make payouts when fields are too wet to plant.

North Dakota’s short growing season makes it particularly susceptible to losing acreage to planting delays: Crops are planted later in the spring than other parts of the Corn Belt and frost comes earlier in the fall. Flooding in the Red River Valley, especially when snowmelt empties into tributaries, is often a deciding factor.

Gro Intelligence recently added to its data platform the Global Historical Climatology Network (GHCN), which allows Gro users to model the impact of weather events on crops. The data, comprising daily weather observations from more than 75,000 stations, shows snow depths in North Dakota and Minnesota to be at their highest levels in the past 12 years.

That much accumulated snow suggests a worrisome spring-thaw scenario that could keep North Dakota farmers from working their fields. Measures of snow depth in North Dakota from past years show a strong correlation with the amount of acreage that is prevented from being planted, as snowmelt raises river levels and causes flooding. (See chart below.) A similar scenario can be expected this year. Even areas that do get planted, if they’re delayed, could suffer from lower corn yields, or farmers may choose to forgo corn and plant faster-maturing soybeans instead.

Adding to the concerns about flooding, soil moisture in almost the entire Corn Belt is in the 99th percentile, according to the National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center, suggesting that snowmelt will largely run off from already water-logged soil. On a positive note, waters of the Red River are relatively low, based on readings taken at Fargo, North Dakota, by the United States Geological Survey, suggesting the river may be able to handle some of the snowmelt.

Flooding Zones

Last week’s “bomb cyclone” brought heavy rains and snow to the central United States. In Iowa and Nebraska, the rains coincided with spring thaw, and many river levels in those states set new records. Livestock was washed away, bridges and roads were wiped out, and thousands of people were evacuated from their homes. At least three people were reported killed as a result of the storm.

It’s too soon to know to what extent this year’s crops in central states will be affected by the storm damage, since grain farmers in the Corn Belt don’t start putting seed in the ground until mid-April. The storm has had other impacts on the farm economy, however. High water levels on the Mississippi River have snarled logistics for processors, including soybean crushers and ethanol producers. Washed out roads and rail lines, along with limited availability of river barges, have frustrated exporters looking to get their product to the US Gulf for shipment.

Farther north, flooding is still expected to come to the Red River basin, which could affect how much acreage is planted and in what crops. The Red River, also called the Red River of the North, defines much of the border between North Dakota and Minnesota, and its northward flow makes it especially susceptible to spring floods. Over 100,000 square miles in North Dakota and Minnesota, along with Canada’s Saskatchewan and Manitoba provinces, drain into tributaries of the Red River.

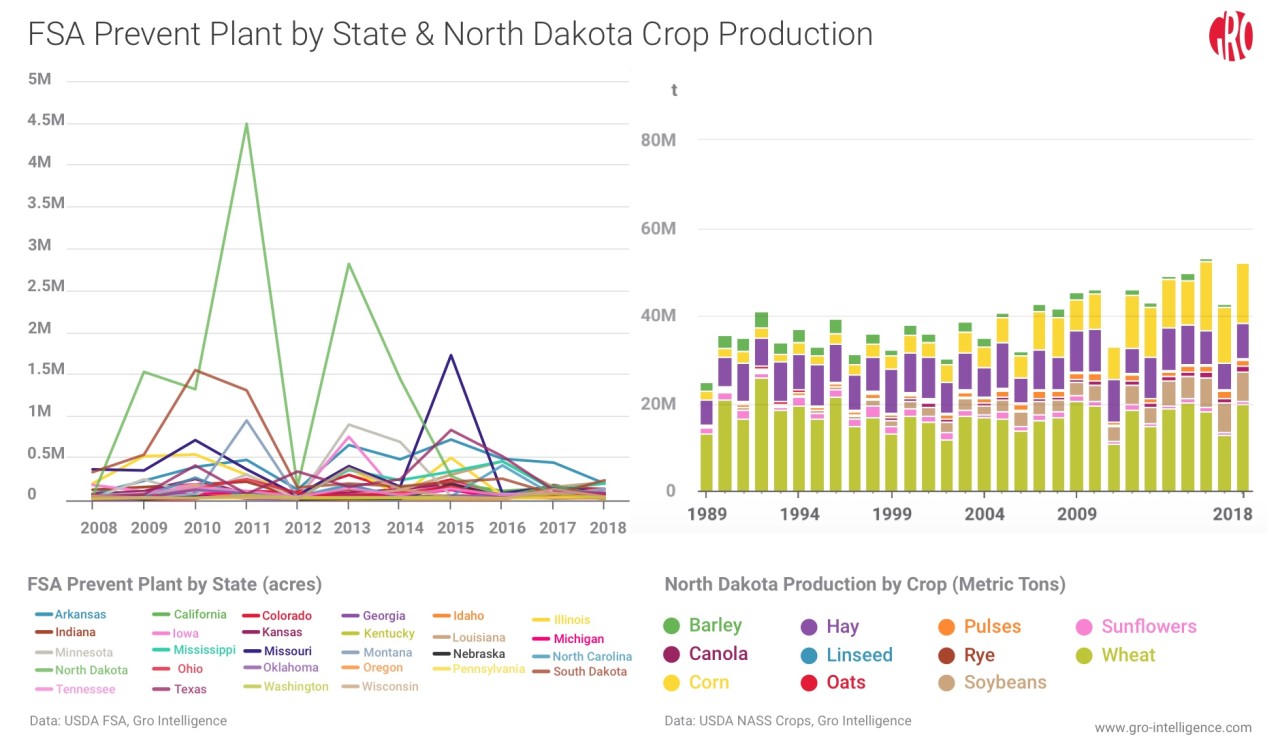

Spring snowmelt can push the Red River over its banks when the flow into the still-frozen North is blocked. In 2011, 4.5 million acres in North Dakota were prevented from being planted. Significant spring floods were seen in both 2009 and 2010, when North Dakota lost 1.5 million and 1.3 million acres, respectively, and helped set the stage through increased soil-moisture levels for the 2011 big floods. Although 1 million to 4.5 million acres represent a modest percentage of North Dakota’s total acreage, the loss of millions of bushels of corn has an outsize impact on the US supply/demand balance sheet and can affect markets.

The USDA’s Farm Service Agency reports prevent-planted acreage data monthly starting in August and ending in January with final figures. In the 12 years since the USDA began releasing the data, prevent-planted acreage ranged from 1.2 million to 9.6 million acres. North Dakota, Texas, and Missouri have been the most significant drivers of acres lost to prevent-planting, with North Dakota leading in four of the top six years.

The left chart above shows the number of acres (left axis) in US states that were prevented from being planted by severe weather or wet conditions, according to the USDA Farm Service Agency. North Dakota stands out for contributing the largest number of prevent-plant acres, usually because of flooding by the Red River. The right chart shows North Dakota’s historic agricultural production by crop, measured in tonnes. Wheat, corn, and soybeans, along with hay, are the state’s largest crops.Planting Intentions

On March 29, the USDA will release its Prospective Plantings report summarizing farmers’ early-March planting intentions. How farmers divide their acreage among corn, soybeans, wheat, and cotton will be a key driver of the new 2019/20 marketing year’s supply and demand estimates, and whether the past year’s price weakness has caused a shift to nontraditional crops or reduced total area planted will be an important focus. Still, these are farmer intentions. Spring weather will dictate whether those plans are carried out.

GHCN’s snow-depth data proves to be a strong indicator of prevent-plant acreage in North Dakota. When snowpack gets too high, the amount of water released when temperatures rise can overwhelm the river system. Using end-of-February GHCN snow-depth data in the Red River tributary regions of North Dakota, Minnesota, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan, we charted average snowpack levels for tributary regions in each state and province. The data shows North Dakota and Minnesota snowpack levels at their highest point in the past 12 years. The Manitoba snowpack is in the top three for those years, while the level for Saskatchewan is in the middle of its 12-year range.

River gauge heights provided by the USGS give an indication of how high river levels are before the spring thaw starts. This year, the river gage level at Fargo was at 14.43 feet at the end of February, suggesting there could be fewer acres lost to prevent-planting than in previous years. By comparison, in 2011, when North Dakota prevent-planting reached 4.5 million acres, the river gage height at Fargo was 15.91 feet at the end of February.

Gro Intelligence recently added to its data platform the Global Historical Climatology Network (GHCN), which allows Gro users to model the impact of weather events on crops based on daily weather observations from more than 75,000 stations. The left chart above shows that snow depths measured at Cavalier, North Dakota, for 2019 (darker blue line) are at their highest levels in years. The right chart shows Red River gage heights in feet, as measured by the USGS at Fargo at the end of February. The river height for the current year was at the low end of the recent years’ range, suggesting the river may be able to handle some of the snowmelt.Crop Switching

Even if producers are able to get their seeds sown in time, planting delays can lead to shifts among what crops are planted. Corn, for example, is susceptible to yield losses if it pollinates in hot and dry conditions, so farmers must get the crop planted so that it pollinates before the summer heat. Indeed, the amount of corn ultimately planted in North Dakota fell below farmers’ initial planting intentions in each of the state’s five major prevent-plant years since the USDA began reporting the data in 2007. In three of those five years, North Dakota’s soybean area was flat to higher compared with initial planting intentions. Soybeans have a shorter growing season and don’t share corn’s sensitivity to heat. Those past crop shifts suggest that a delay in getting corn planted forced farmers to switch acreage from corn to shorter-season soybeans.

Delayed planting also can hurt corn yields, as was seen in four of North Dakota’s five major prevent-plant years. Many farmers apply nitrogen fertilizer in the fall, and floods leach that nitrogen from the soil. Yields on soybeans also tended to be below trend in most of the state’s five big prevent-plant years. On the other hand, with the exception of 2011, flood years have actually produced strong wheat yields (8 to 16 percent above trend) for the areas that managed to be seeded, suggesting that the additional moisture and delayed planting date may have benefited the crop.

The chart above shows North Dakota’s corn yields (bushels per acre, left axis) over the past 30 years. The yield trend is indicated with the dotted line. Corn yields tend to decline in years when floods delay farmers from getting seeds into the ground (indicated by orange dots). Many farmers apply nitrogen fertilizer in the fall, and floods leach that nitrogen from the soil.Conclusion

As we enter the spring thaw, near-record snowpack covers much of the northern Midwest, and soil moisture is in the 99th percentile in nearly the entire US Corn Belt. As a result, major flooding is almost assured, setting the stage for planting to be significantly delayed this year. States like Iowa and Nebraska, where floods ravaged vast tracts of farm country this past week, may have time to dry out before seeds need to go into the ground. Those states may also be locking in good subsoil moisture levels that will benefit crops in the upcoming season. Spring planting weather will tell. Over the past decade, Iowa and Nebraska have not been big contributors to nationwide prevent-planted acreage. Instead, it’s North Dakota that has regularly lost millions of acres to prevent-planting when the Red River floods. That risk is very present for the current year as well.