Indiana Farmland Values Fall for Fifth Straight Year

Farmland values are an important indicator of the health of the U.S. farm economy. Farmland accounts for the vast majority of the assets of the farm sector. As farm incomes have slid we have carefully watched indicators of farmland values for clues to how well they are holding up. Purdue’s farmland value survey is one such indicator. It measures respondents views of the value of different categories of Indiana farmland. The most recent survey shows that farmland values have continued to decline from their 2014 peak.

Indiana Farmland Values Down from Peak

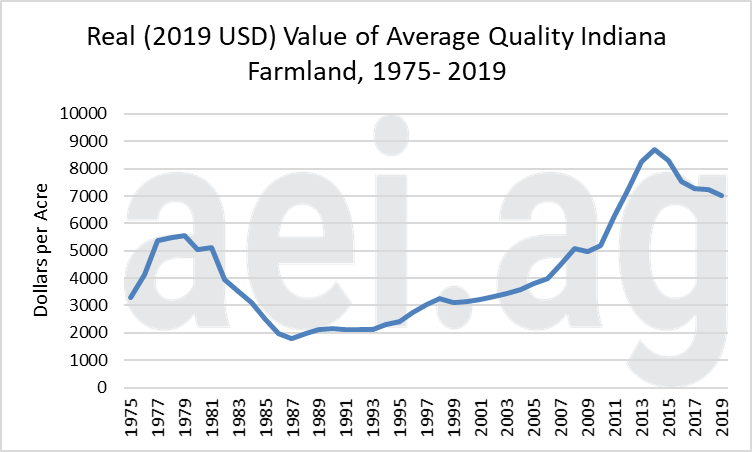

Average-quality Indiana farmland declined only slightly from 2018 to 2019, but have been on a downward trend since 2014. After reaching nearly $8,000 per acre in 2014, the value of average quality Indiana farmland values has fallen 12% to $7,011 per acre in 2019. Over that same time, high-quality land fell by 15%. These declines are relatively large by recent standards but pale in comparison to the 1980’s when land average and high-quality land values fell by 57% and 55% respectively.

Figure 1 shows real (inflation-adjusted to 2019 dollars) average-quality Indiana farmland values reported by the Purdue survey. One can observe two clear peaks in the series. The previous period of decline saw farmland value fall for 6 straight years from 1981 to 1987. The current streak of declines stands at 5 years, but to date has seen much more modest declines than in the previous downturn.

Figure 1. Real (2019 USD) Value of Average Quality Indiana Farmland, 1975-2019.

Low Capitalization Rates Persist

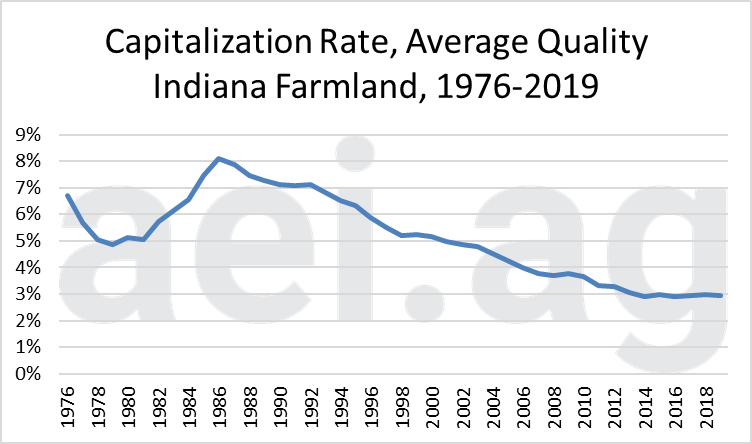

One of the reasons that the current situation has resulted in more modest declines is that interest rates have remained low. In the previous downturn, both income and interest rates were changing rapidly.

The capitalization rate implied by Indiana farmland values and cash rental rates is shown in figure 2. This is calculated by dividing the cash rental rate by farmland values. The current capitalization rate has remained near 3% for several years now. In the last major downturn, capitalization rate started increasing as farmland values fell faster than cash rental rates. The ratio peaked at slightly over 8% in 1986 before starting the downward trend that it has been on ever since. Since 2011 the capitalization rate has been 3.2% or lower and has corresponded to the low interest rates seen in the broader U.S. economy.

Figure 2. Capitalization Rate for Average Quality Indiana Farmland, 1976-2019.

Farmland Price Moderates Slightly Relative to Revenue

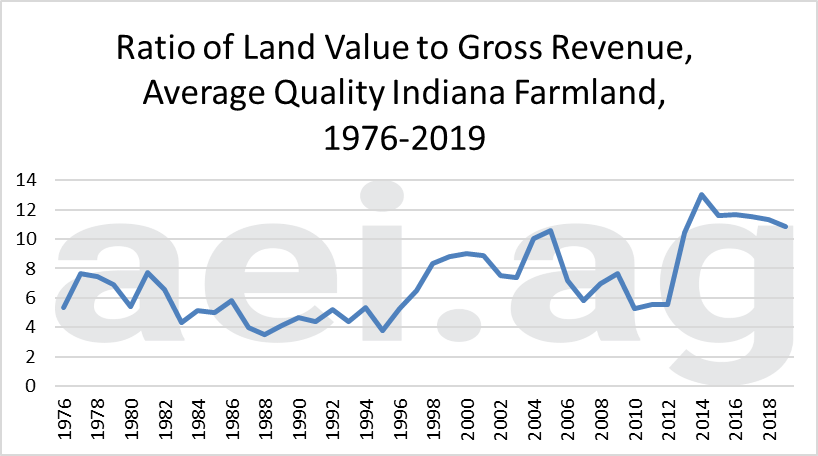

One of the reasons that farmland values have softened is that cash rents have been falling. This decline has coincided with the reduced income that farmers can expect farmland to generate. Figure 3 shows the ratio of farmland value to the gross revenue that farmland is expected to generate. It is a type of price to sales ratio. It was calculated by dividing farmland value by the expected revenue associated with the land. Expected revenue was calculated by multiplying the expected corn yield in bushels per acre by the market year average price for corn in Indiana. The 2019 estimate of corn yield was 175 bushels per acre and the market year average price was $3.70 per bushel as estimated in the July WASDE report.

This figure shows that today the price to revenue ratio is 10.82. It has fallen since reaching a peak of 13.04 in 2014, but remains elevated by historical standards. For instance, even in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s the ratio did not climb above 8. This is in large part likely due to the general decline in interest rates that occurred since the 1980’s. With lower interest rates, market participants do not discount future earnings as heavily as they would with higher interest rates. Given that rates have remained relatively stable in recent years, it appears clear that farmland investors have begun to ratchet down expectations for the revenue and net returns that can be generated from a farmland investment.

Figure 3. Ratio of Land Value to Gross Revenue, Average Quality Indiana Farmland, 1976-2019.

Where We Stand Relative to the Past

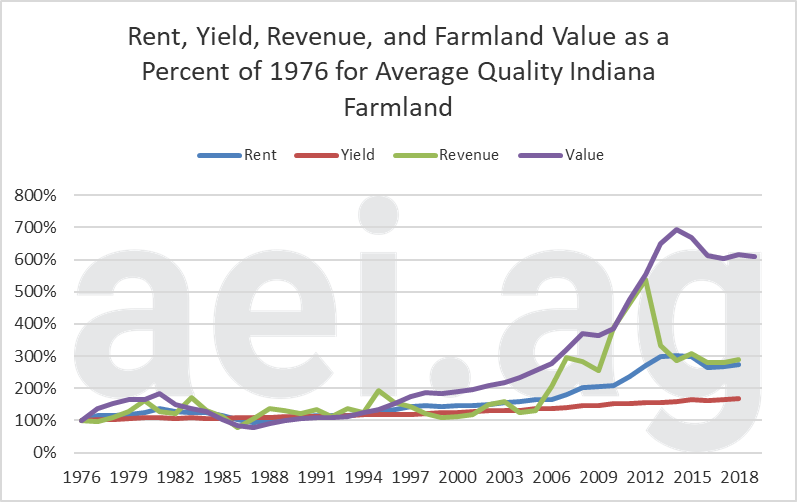

The final graph in Figure 4 shows how rent, yield, revenue, and farmland value have evolved since 1976. In this case, everything is shown relative to 1976. For instance, the yields associated with average quality Indiana farmland have increased steadily over the time period and now stand at 171% of 1976 levels. This 71% increase over the time period amounts to a compound growth rate of 1.3%. We would suspect that many people would have guessed that the growth rate would have been larger, but that is what was calculated from the data.

Cash rents, shown in blue, have increased by 168% over this time period for a compound growth rate of 2.3%. That rents have grown faster than yields is not surprising, because the growth rate was calculated on nominal values which are subject to inflation. The green line represents the change in revenue. After increasing much faster than rents in the mid to late 2000’s, revenue has declined to come back to nearly the same level of total increase as rents.

Figure 4. Rent, Yield, Revenue and Farmland Value as a Percent of 1976 Levels for Average Quality Indiana Farmland.

The final line to discuss is farmland values, which are shown in purple. Even after the declines of the last 6 years, they have increased 510% since 1976 (again in nominal terms). This again shows the power of the falling interest rate environment over the majority of the time period and the very low interest rate environment of recent years.

Wrapping it Up

Farmland is a critically important asset in the farm sector. According to ERS, it is projected to account for 83% of all farm sector assets in 2019. Changes to farmland values can significantly impact the equity position of the sector. As the U.S. farm economy has struggled through a period of low incomes, farm debt has increased. Much of the increased debt load has come in the form of debt backed by farm real estate. As such, changes to these values impact the collateral position of many agricultural lenders and the equity positions of farmers.

The 5 straight years of declines in Indiana farmland values indicates how generally poor the agricultural economy has been in recent years. There has only been one time since 1976 when farmland values have fallen this many years in a row, the 1980’s. One key difference between then and now is that the declines were much, much steeper in the 1980’s.

When the more extreme declines occurred, both incomes and interest rates were moving unfavorably. At present, it has been only incomes moving unfavorably for farmland owners. The declines in Indiana farmland values have moderated a bit after moving downward more sharply in the first part of the downturn. This likely reflects that opinion that revenues may be stabilizing.

Whether or not revenues stabilize will likely be the deciding factor in determining the immediate future movements in farmland values. On one side of the ledger are the recent MFP payments which will provide a welcome shot of liquidity, particularly in states like Indiana. A quick perusal of county-level MFP payment rates found only one in Indiana with a payment rate below $50/acre and many in the $60 to $70/acre range. Some counties in other states did not fare as well.

On the other side of the ledger, the trade war continues to exact a significant toll on the economic prospects of the farm sector. That USDA has earmarked $23 billion of trade adjustment payments ($8.59 billion in round 1 and $14.5 billion in round 2) says a lot about the magnitude of the problem in the short term. Whether this money has been distributed appropriately/equitably in the farm sector is another major question, but that is probably for another day.

If the trade war is not resolved by next planting season, one can expect that the revenue associated with farmland will likely fall further, barring another major weather scare and/or additional trade aid. As we have argued earlier, (1, 2, 3) payments of this magnitude will likely be necessary to keep the farm economy and farmland values afloat if the trade war persists. One can hope that a resolution may come, but at present, the finish line appears nowhere in sight.

In the longer term, the damages of the trade war are likely much greater than even those suggested by the large MFP payments. The trade war is clearly sending signals to our competitors for the Chinese market that they should expand production. Increased expansion in these areas, particularly in South America, will create a price that will be paid for by U.S. farmers and U.S. farmland investors for many years to come.

Like what you read? Click here to subscribe to AEI’s Weekly Insights and receive our free, in-depth articles in your inbox every Monday morning.

But wait, there’s more: click here to visit the archive of our articles – hundreds of them – and to browse by topic. We hope you will continue the conversation with us on Twitter and Facebook.

Source: Brent Gloy, Agricultural Economic Insights