Farm Bill-Conservation Title, Update from USDA’s Economic Research Service

On Monday, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service (ERS) published an overview of the Conservation Title of the 2018 Farm Bill. Today’s update looks at a couple key points from the ERS summary.

After highlighting several changes to specific programs in the Conservation Title, ERS turned to a broader focus on the economic implications of the new provisions.

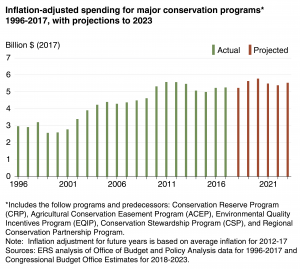

The ERS update explained that, “For FY2019-FY2023, the CBO [Congressional Budget Office] projects mandatory spending on farm bill conservation programs that is slightly higher than projected baseline spending (spending under an extension of 2014 Farm Act programs, without modification, through 2023). For the five largest conservation programs (and predecessors), inflation-adjusted spending increased under both the 2002 and 2008 Farm Acts (2002-2013, see chart below), but was lower under the 2014 Farm Act (2014-2018). CBO projections suggest that the 2018 Act could provide slightly higher funding, on average, than under the 2014 Act. Although program funding is mandatory (does not require appropriation), spending in future years is subject to congressional review and, under past farm acts, has sometimes been reduced from specified levels.”

“Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018: Highlights and Implications. Conservation: Title II.” USDA’s Economic Research Service (https://goo.gl/hNh4Rx, February 11, 2019).

In addition, ERS stated that, “While overall conservation funding is roughly equal to baseline levels for FY2019-FY2023, the 2018 Act shifts funding among programs. The acreage enrollment cap in the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) is replaced with a funding cap that implies lower spending in the future. Contracts signed under the acreage-limited CSP will continue; contracts that expire before December 31, 2019 can be renewed. Going forward, the 2018 Act sets spending limits of $700 million for FY2019, increasing to $1 billion by FY2023. CSP funding was $1.32 billion in FY2018 (estimated) and was projected to be roughly $1.75 billion per year, on average, for FY2019-FY2023 according to the CBO.

Over the next several years, as spending for existing CSP contracts ramps down and spending on new contracts ramps up, CSP spending will eventually reach an overall lower level of spending commensurate with new limits.

“In contrast, the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) funding is increased from $1.75 billion in FY2019 to $2.025 billion in FY2023, compared to an averagebaseline of $1.75 billion over FY2019-FY2023. Funding is also increased for the Agricultural Conservation Easements Program (from $250 million to $450 million annually) and the Regional Conservation Partnership Program ($100 million to $300 million annually). Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) funding is projected to decline (a total of -$189 million) over FY2019-FY2023.”

Monday’s update also pointed out that,

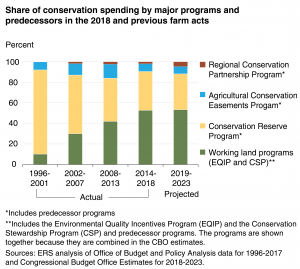

Changes in major conservation program funding under the 2018 Act will effectively halt the shift toward increasing the share of conservation funding for working land programs that began with the 2002 Act and continued under the 2008 and 2014 Acts.

“While funding has shifted toward working land programs in every farm bill since 2002, the size of the shift has declined in each subsequent farm act. Under the 2014Act, working land program funding accounted for a majority (53 percent) of major conservation program funding for the first time. Under the 2018 Act, spending for working land programs will again account for about 53 percent of the five largest programs. (Working land programs are defined here to include EQIP and CSP. Other programs can also support working lands. Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP) can help preserve working agricultural land that would otherwise be developed. Some CRP continuous signup practices (e.g., filter strips) may also complement crop production. Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP) can fund a wide range of practices.)”

“Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018: Highlights and Implications. Conservation: Title II.” USDA’s Economic Research Service (https://goo.gl/hNh4Rx, February 11, 2019).

ERS also explained that, “While the overall acreage cap for the Conservation Reserve Program is increased from 24 million to 27 million acres under the 2018 Act, other changes could limit the size of annual rental payments and may reduce enrollment incentives. Annual rental rates could be affected by two provisions. The first affects the determination of county average soil rental rates (SRRs). County-average SRRs, which were equal to the county-average rental rate for non-irrigated cropland under previous farm acts, would be set 15 percent below county-average rates for general signup and 10 percent below county-average rental rates for continuous signup. Because county-average SRRs underlie CRP limits on annual rental payments, these provisions could result in rental payments as much as 15 percent lower for general signup and 10 percent lower for continuous signup. Actual limits established for CRP implementation can also include adjustments to the county-average SRR, including adjustments (up or down) for field-specific soil quality. The second new CRP provision applies only to land that has already been in CRP. For these lands, an overall countywide ceiling on annual rental rates would also apply. Annual rental rates could not exceed 85 percent of the county average rental rate (not the county-average SRR) for general signup and 90 percent for continuous signup.”