A Wild Ride for Exchange Rates in 2020

In the early weeks of the COVID pandemic, we noted that exchange rates would be an important factor to watch in 2020. After surging higher, the Dollar has drifted lower in recent weeks. This week’s post reviews the latest data and potential implications for U.S. agriculture.

Dollar Higher Shoots Higher… At Least Initially

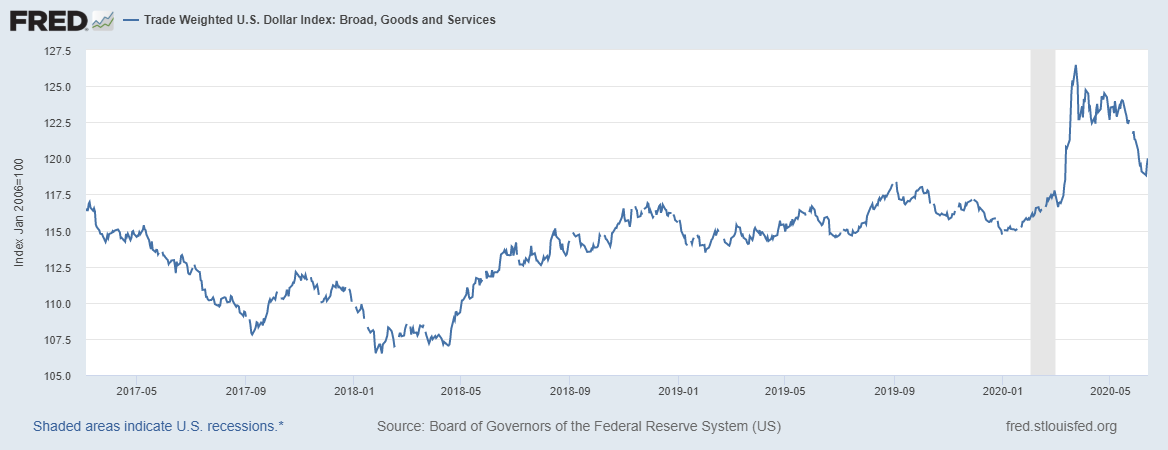

Figure 1 shows a trade-weighted U.S. Dollar index since 2017. While the Dollar has trended higher in recent years, it surged as global economies braced for COVID shutdowns. Before March, the Dollar rarely exceeded an index value of 117.5. By the end of March, however, the Dollar exceeded 125 and stayed well above 122.5 through May.

Most recently, the Dollar has retracted to around 119. This is considerably weaker than weeks earlier, but remains above pre-COVID levels.

Figure 1. Trade Weighted U.S. Dollar Index. Data Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data, St Louis Federal Reserve Bank (data here).

Implications of Higher Dollar

Figure 1 shows the Dollar’s cost relative to dozens of currencies, weighted by trade activity. While the data are helpful, each product or commodity faces unique exchange rate conditions based on trade partners and activity.

To account for the varied conditions, the USDA reports an export exchange rate index for each commodity. These data were updated in May 2020, before the Dollar (figure 1) turned lower.

Table 1 shows the USDA’s forecast of 2020 conditions relative to 2016 and 2019 levels. Overall, row crops have been the hardest hit. Since 2016, the trade-weighted exchange rate for corn and wheat has increased 6%, up 10% for cotton.

Meat exports have been less vulnerable. The forecasted 2020 exchange rate index for beef is lower than 2016 levels, and only slightly higher than in 2019.

Again, the implications of a stronger (or weaker) Dollar varies across agricultural commodities.

Table 1. Trade-Weighted Exchange Rate Index for U.S. Ag Commodities (Exports). Data Source: USDA and aei.ag Calculations.

Soybeans and Corn

For agriculture, an international buyer of soybeans, for example, would first use their local currency to purchase U.S. Dollars, and then buy the grain. Even if the farm-level prices are unchanged, an adjustment in exchange rates will change the local currency cost. One way of considering how significant exchange rates can be is by converting U.S. farm-level prices to various local currencies.

Figure 1 shows U.S. farm-level prices adjusted to local currencies for Japan (orange), Mexico (gray), and China (yellow). These data are shown as an index (Jan. 2010 = 100) to avoid graphing issues. The first data point to consider is the U.S. price (in blue). This is simply an index of the USDA’s reported farm-level prices.

Now consider Mexico. A stronger Dollar has pushed the currency-adjusted prices higher since late 2014. While U.S. farmers haven’t seen prices significantly change since late 2014, exchange rates have pushed the Peso-adjusted index from nearly 100 to around 175. In other words, farmers aren’t getting more Dollars for a bushel of corn, but that bushel would take more Peso to buy.

Figure 2. Relative Corn Prices, U.S., Japan, Mexico, China. Jan. 2010 =100. Data Source: USDA NASS and FRED (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis). January 2010 – April 2020.

It’s not only international buyers that get economic signals from exchange rates, but also competitors. Figure 2, which shows U.S. farm-level prices received for soybeans expressed in U.S. Dollars and Brazilian Reals. Again, this is not the price that Brazilian farmers are receiving, but a look at U.S. farm prices expressed in Brazilian Reals.

While U.S. soybean prices have trended lower, exchange rates have created a much different story for those selling soybeans in Brazilian Reals. Overall, a weaker Real has translated into the prospect of stable to higher trending prices. So, while U.S. farm budgets have faced declining prices and revenue, the exchange rate – when considered alone- has the potential to send a very different economic signal to Brazilian soybean producers.

Figure 3. U.S. Average Farm Prices Received for Soybeans in U.S. Dollars (left axis) and Brazilian Reals (right axis) – Jan. 2010 to April 2020. Data Source: USDA NASS and FRED (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis).

Wrapping it Up

Exchange rates will be important to watch throughout 2020. After surging higher in March, the Dollar remained strong through May. In recent weeks, however, some of the Dollars strength has eroded.

Exchange rates are complicated because the impacts vary; each commodity faces different international buyers and competitors. Row crop exports have faced the most significant headwinds. Even more specifically, exchange rates have been especially burdensome for Mexican corn buyers, but favorable for Brazilian soybean growers.

While exchange rates are typically slow to adjust, we’ve seen big swings in 2020. In recent weeks, the Brazil Real and Mexican Peso have shown considerable strength relative to the Dollar. Looking ahead, a significant source of uncertainty will be where exchange rates go over the next 12-18 months.

Click here to subscribe to AEI’s Weekly Insights email and receive our free, in-depth articles in your inbox every Monday morning.

Looking for more? AEI Premium provides even more insights and content. It is also where you can challenge your thinking with the Ag Forecast Network (AFN) tool. Start your risk-free trial here.

Source: David Widmar, Agricultural Economic Insights